Charlie

Chaplin’s Circus

By Bruce

“Charlie” Johnson

“Charlie

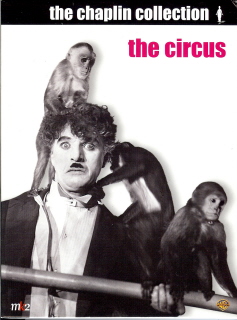

Chaplin’s Circus”, a film originally released in 1928, does a remarkable job

of preserving early twentieth century circus clown history.

In 1969, Chaplin released it with a musical sound track that he composed.

It is available now on DVD for us to study and enjoy.

During the

opening title sequence of the musical version, Charlie Chaplin can be heard

singing one of his compositions. Singing

was definitely a part of the American circus in the 1920’s.

During that decade many shows started with a big production number or

spec that included a song by a prima donna who was seated on a horse or

elephant. Singing clowns had been

very popular during the 1800’s, but had declined after the turn of the

century. Here are some of the last

performances by singing clowns that I have been able to locate:

James Swetham (1897 Great American Shows), Peco and Bosco (1898 J.

Augustus Jones One-Ring Show), an unidentified clown (1900 The Great Rhoda Royal

Australian Railroad Shows), Albert Gaston (1905

Frank A. Robbins Circus), Miss Kate Dooley (1907 The Great Van Amburg

Shows), Millie Clio (1908 Frank A. Robbins Circus), Mary Koster (1909 Frank A.

Robbins Circus), Slivers Oaks (1911 Frank A. Robbins Circus), and William Langer

(1912 Howe’s Great London Shows). These

were all American circuses despite the titles.

Some proprietors thought giving their show a foreign name gave it a

greater aura of quality.

The

opening title sequence of “Circus” ends with a shot of a star in the center

of a white circle. The shot irises

out to reveal that the circle is a paper covered hoop being held by a clown.

The circus term for a paper covered hoop is “balloon.”

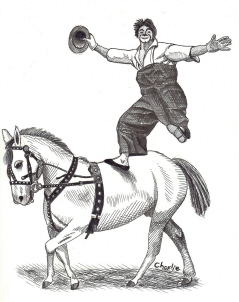

Suddenly a beautiful young equestrienne, played by Merna Kennedy, bursts

through the center of the hoop and lands on the back of her horse.

Clowns often served as “object holders” for equestrian acts.

In addition to balloons, a clown might hold one end of a streamer to

serve as hurdle for the rider. A

clown holding a balloon for an equestrian became one of the iconic images of the

circus and was used on many posters and program covers.

When Merna

dismounts from her horse at the end of the act, the clowns rush into the ring

and begin playing “ring around the rosey.”

That isn’t quite accurate. During

this era clowns did participate in equestrian acts.

They were careful not to be distractions while the rider was performing

tricks, and then would do carefully prepared bits to give the rider a breather

or while horses were being exchanged. Then

when the act concluded the clowns would pose with the rider to accept the

audience’s applause.

We first

meet Charlie in the midway of a county fair where he is unfairly accused of

being a thief. Fleeing the police,

Charlie runs into the circus tent, trips over the ring curb, and trips over the

ring curb again going in the opposite direction.

He is thrown out of the circus, even though he is an instant success with

the audience. This is a

reenactment of the Tom Belling story. Belling

was an American acrobat and equestrian performing in

Germany

with a European circus in

1869. He was suspended for a

performance as punishment for mistakes he made during his act.

Unable to participate in the circus he got bored during the show time.

He put on clothes that didn’t fit properly and donned a wig backwards

to amuse his friends in the dressing room by impersonating the manager of the

show. When the manager discovered

him, Belling ran into the tent trying to escape.

He fell over the ring curb into the ring.

In trying to exit, he fell over the ring curb again.

The delighted audience yelled Auguste, which is German for fool.

The manager insisted that he continue portraying the character and

according to circus legend a new type of clown character was born.

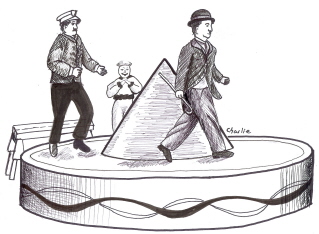

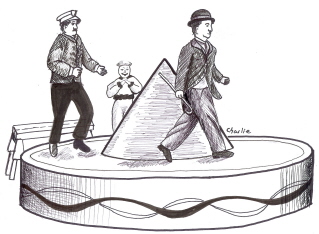

In this

movie, while still fleeing the police, Charlie returns to the tent where the

clowns are performing the Revolving Table act.

The clowns try to jump up on a large spinning platform and run in place

like they are on a treadmill. Because

they also have to contend with centripetal force they often fall and are thrown

off. Chaplin and a policeman jump

onto the table and continue their chase with hilarious results.

This act was introduced by Bert Mayo on the 1912 Sparks Circus.

It was a great success and was quickly copied by other circuses.

Between 1913 and 1925 most circuses included the Revolving Table.

Often shows had one in each of their three rings.

A review of the 1914 Al G. Barnes Circus in Billboard

magazine described the act this way, “Circus

Roulette Wheels, or revolving tables.

Watch the rubes try to ride them – you’ll laugh.

You’ll also marvel at the skill with which dogs jump over the hurdles

while riding the wheels. After the failure of many men, who try to ride the

wheels, Tot and Tiny, world’s smallest ponies, ride them at top speed with the

greatest of ease. It’s a wonder

feature.”

When I

toured with the Funs-A-Poppin Circus in 1982 and 1983, I saw Heidi Wendamy use a

small revolving table in her dog act. The

kids in the audience always started laughing when her dog Babe jumped onto the

table and joyfully trotted in place. Sometimes

Babe would start racing which made the table spin faster and the laughter would

build.

Often

actual circus clowns are hired for circus movies.

However, the clowns in Chaplin’s film are all members of his stock

acting troupe. The Old Clown is

Henry Bergman who played leading roles in other Chaplin movies, including Hank

Curtis in The Gold Rush. He also

worked creatively with Chaplin behind the camera.

The other clowns are Albert Austin, Henie Conklin, Armand Triller, John

Rand, and Harry Crocker. They all

had played roles in Chaplin’s short films and earlier features.

Crocker played additional roles in “Circus.”

He was also the Disgruntled Prop Man demanding their back pay, and he was

Rex, the wire walker, Chaplin’s romantic rival.

The clowns

may not have had circus experience, but they performed acts based on those

performed by clowns in circuses of that era.

In this

film, Charlie is invited to audition to be a clown with the circus.

First the clowns demonstrate a routine called William Tell.

A clown archer is going to shoot an apple off his assistant’s head.

However, before he has a chance to attempt the stunt his hungry assistant

eats the apple. When Charlie

attempts to repeat the act he is dismayed by finding a worm in the apple.

He decides to perform the act using a banana, which does not fit the

famous legend. The bonus features in

my DVD copy of “Charlie Chaplin’s Circus” includes a film clip of two

unidentified circus clowns performing the William Tell act in 1900.

Next the

clowns demonstrate the Barber act, another classic clown routine, to Charlie

during the audition. (The Barber act

was performed on the 1908 Campbell Bros. Circus and the 1917 Coop and Lent

Circus.) In “Circus”, two

barbers are in the center of the ring with chairs.

A single customer enters. Each

barber directs the customer to their chair so he ends up pacing back and forth

between the two chairs. Finally he

throws up his arms in frustration. After

handing the first barber his hat and cane, he sits in the first chair.

When the second barber directs him over to his chair, the customer agrees

to move. When the first barber gets

down on his knees to beg him to move back, the customer declares that he is

going to stay where he is. Both

barbers get buckets of whipped shaving soap and large brushes.

The second barber stands between the two chairs, with his back to the

first barber, and begins lathering the customer’s face.

In retaliation for stealing his customer, the first barber kicks his

co-worker in the seat. He wipes a

brush full of soap across the second barber’s face when he turns around.

The first barber yanks the customer over to his chair and begins to

lather his face. The second barber

retaliates by hitting his co-worker in the face with a brush full of soap.

The barbers take turns brushing soap in each other’s face.

The camera

cuts to the Ringmaster ordering Charlie to take the role of the first barber and

repeat the act. Everything goes fine

until it is time for Charlie to get hit with the soap filled brush.

He dodges out of the way. His

partner explains that he has to hit him. Charlie

agrees, but automatically ducks again. The

Ringmaster orders him to stand still. The

second barber hits him with the brush, and then continues to slap on more soap.

Charlie is so shocked that he forgets what he is supposed to do.

His partner tells him, but he doesn’t understand.

Charlie turns towards the Ringmaster who yells for him to hit his partner

with soap. Because Charlie’s face

is covered with so much soap he can’t see that his frustrated partner sat down

in a chair. Charlie flails in the

air with brushes full of soap. His

partner stands up and takes Charlie’s hand so he knows where to aim the soap.

Just as Charlie begins his swing, the Ringmaster charges into the ring to

tell Charlie he has failed the audition. Charlie

hits the Ringmaster full in the face by mistake.

Charlie makes wide gestures while trying to explain that he can’t see,

unintentionally hitting the Ringmaster in the face with soap two more times.

The Ringmaster orders Charlie to get out, and stay out.

Although

Charlie failed his clown audition, he is hired as a prop man.

He is so inept that he becomes the comedy hit of the circus.

Again, this has precedent in early twentieth century circus and

theatrical clowning. Marceline Orbes,

resident clown at

New York

’s Hippodrome Theater,

provided inept help to the prop men. For

example, when the group of prop men assembled the circus ring curb they inserted

pegs to hold the sections together. Marceline,

following them, would remove the last peg and take it to the first man in line

to use for the next section. Following

a brief retirement from clowning to make an unsuccessful attempt at running his

own restaurant, Marceline toured with the 1920 Sells Floto Circus.

In this

film, Charlie is no longer pursued by the police once he is hired by the circus.

However, now he is tormented by a mule that keeps chasing him.

Just about every circus in the first quarter of the twentieth century

featured at least one clown act with a mule, and many had several different mule

acts. In 1923, eight-year-old Mark

Anthony attended a circus in

Hartford

,

Connecticut

.

Mark said, “There was a clown working a gag with a donkey, and at that

moment, I knew I was going to be a clown.”

In one

scene of “Charlie Chaplin’s Circus”, the mule begins bucking by kicking up

its hind feet. That is something

these animals do naturally. Clowns

based acts on mules trained to buck on cue.

A very popular act during this era was known as the Football Mule.

A ball similar to a beach ball would be placed behind a mule.

When it bucked the ball would go sailing into the audience.

The clowns would retrieve the ball so the mule could kick it again.

Another common act was the Unrideable Mule.

A clown would enter riding a mule, and invite audience members to attempt

to ride the animal. After a

volunteer mounted the mule, the clown cued it to buck, sending the audience

member crashing to the ground. (This

act is no longer performed because of the potential for an audience member being

injured.) An act frequently listed

in circus programs of this era is clowns riding mules in hurdle races.

It was also common for clowns to drive a cart pulled by a mule.

Since singing was an important part of the circus, it was naturally

burlesqued by the clowns. Often a

prima donna’s performance would be followed by the clowns presenting a singing

mule.

Charlie

Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Buster Keaton are often considered the triumvirate of

silent comedy. They each were highly

successful professionally and artistically.

Comparing their work reveals that while they had their own distinct

performance styles they influenced and inspired each other.

Lloyd, often referred to as the King of Daredevil Comedy, released

“Safety Last”, his great thrill comedy masterpiece, in 1923.

The climax of Lloyd’s movie is a long extended human fly sequence

filmed on the side of a tall building in

Los Angeles

.

The movie provided one of the most famous silent movie images, Harold

Lloyd hanging from the hands of a clock that has started to tilt away from the

top of a sky scraper. The success of

“Safety Last” inspired Chaplin to make his own thrill comedy concluding with

a routine filmed high in the air.

The circus

was a natural setting for a high comedy thrill routine because this was an era

of clowns performing in aerial acts. Walter

Guice was known for his clown aerial horizontal bar act that he performed with

various partners from 1906 until 1939. The

1919 edition of the Sells Floto Circus featured Comedy Bar acts by the

Livingston Trio and by Stokes & Engine.

The same show had a comedy revolving ladder act by Hendricks &

Livingston. That year Bert Doss joined the Flying Wards trapeze act as a clown.

The Sells Floto Circus had a comedy aerial bar act performed by the Blanche

Brothers in 1920. Jim White clowned

in John Tunello’s high ladder act with the 1921 Lincoln Bros. Circus.

There was a specific precedent for clown high wire acts.

Tom Bosco had performed a comedy high wire act on the J. Augustus Jones

One-Ring Show in 1898. Freddie Biggs

performed a comedy high wire act as a clown from 1913-1920 on the Sells-Floto

Circus. Chaplin decided to end his

movie with a comedy high wire act. Then

he worked backwards to create a script motivating his presence on the wire.

For the

film, Chaplin wanted to add a further complication that he needed to deal with

while trapped on the wire without an avenue of escape.

He decided to have a group of monkeys swarm onto the wire.

Clowns of this era worked with a variety of animals, including monkeys.

In 1871 William Conrad performed a clown act with dogs and monkeys on the

John Robinson’s Circus. The Norris

and Rowe Show presented an unusual act in 1901; a fire department made up

entirely of dogs and monkeys that saved other animals from a burning building

and then extinguished the flames. In

1919 the Sells Floto Circus featured a clown fire department with monkey-manned

fire apparatus and safety nets. According

to Billboard magazine, “Because of their excellent simian support

in this number, the clowns have to work extraordinarily hard.”

Three shows featured clowns and monkeys in 1925, the year before Chaplin

began filming “Circus”. Clowns

on the Lee Bros. Circus presented high diving dogs and monkeys.

The Sparks Circus clown alley performed walk arounds with pigs, geese,

chickens, and a monkey. The most

important was the Al G. Barnes Wild Animal Circus which included a monkey

performing a wire walking trick known as the Slide For Life.

The winter

quarters for the Al G. Barnes Wild Animal Circus were in

Southern California

and they spent part of each

year touring the region. The show

developed a working relationship with many of the movie studios and rented

animals for use in films. (The

circus equipment also was rented to studios.)

Even when the show was touring other parts of the country, they would

send animals back to Los Angeles for film appearances.

For example, in 1926 Austin King, a horse trainer, left for a month to

handle a herd of zebras trained to pull wagons on Cecil B. DeMille’s film

“The King of Kings”. (In the

film the zebras were hitched to chariots.) It

is logical to assume that Chaplin obtained the mule, monkeys, and other animals

he used in his film from the Al G. Barnes Wild Animal Circus.

“Shrimp”

Settler performed a clown act with a dog and monkey on the Al G. Barnes Wild

Animal Circus in 1917. During the

1920’s the Al G. Barnes Wild Animal Circus featured acts with monkeys,

sometimes presented by clowns. Describing

the 1922 Al G. Barnes Wild Animal Circus performance, Chang Reynolds wrote,

“Nearing the end of the program several monkeys scattered about the arena

performed clever comedy stunts on the trapeze and wire.”

These are probably the monkeys that appear on the wire in “Charlie

Chaplin’s Circus”.

Chaplin

produced, wrote, directed, and starred in “Circus.”

In recognition of his amazing versatility, artistry, and skill he was

honored with a special Academy Award at the first

Academy

of

Motion Picture Arts

and Sciences banquet.

(They weren’t yet known as the Oscars.)

Not only

does this movie preserve the type of circus clowning common in the 1920’s, but

it also preserves the work of one of the most influential clowns in history.

Chaplin’s silent movies were studied by entertainers world wide and

were important influences upon circus and theatrical clowns in

Russia

,

Europe

, and

America

.

Because Chaplin’s films remain available for our study today, modern

entertainers continue to be influenced by him.

In recognition of his contributions to the art of clowning Charlie

Chaplin was inducted into the International Clown Hall of Fame in 2001.

The 2 DVD

set I purchased of “Charlie Chaplin’s Circus” preserves another glimpse of

clowning in 1928. When the movie had

its West Coast Premiere at Grauman’s Chinese Theater, Syd Grauman produced a

live sideshow and circus as a preliminary performance.

Edwin “Poodles” Hanneford and Pepito, the Spanish Clown, performed in

the circus. A news reel of the

premiere is included as one of the DVD bonus features.

Poodles Hanneford is shown bursting through a large balloon held by

members of his riding act. He was a

world famous equestrian clown who was inducted into the International Clown Hall

of Fame in 1995. Pepito is briefly

shown in the news reel performing as a trainer of two animals portrayed by

people in costumes. Pepito is best

known for his work with Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball.

He taught Lucy his cello routine which she performed in the I Love Lucy

pilot and in the sixth episode (The Audition, November 19, 1951) of the series.

He was also a guest star in the 52 episode (Lucy’s Show Biz Swan Song,

December 22, 1952).

Poodles Hannefore

Many of

the dates in this article came from research by members of the Circus Historical

Society that has been published in their magazine titled Bandwagon.

A series of articles by Chang Reynolds detailing his research into the

history of the Al G. Barnes Circus was extremely helpful.

Many of these circus historians used an entertainment publication titled Billboard as a source of

information. Some of the circus

historians also combed local newspapers for reviews of circus performances and

reports of circus activities. Others

interviewed former circus employees late in their lives and recorded their

memories. I am grateful for their

time in effort in locating and preserving this information about the history of

our art.

Copyright 2011 by Bruce "Charlie" Johnson. All rights

reserved.

This

article originally appeared in the July 2011 issue of Clowning Around, published

by the World Clown Association.

For

information on the World Clown Association go to

www.WorldClown.com